Players take the roles of Javanese royalty who have decided to compete with each other in developing the most fertile area of Central Java in Indonesia. The developers under the command of these Sultans build rice terraces and irrigation fields, found villages, construct palaces and hold festival for the greater glory of their kingdoms. Once the development of Central Java is complete, the kingdom with the greatest prestige in Central Java wins the game.

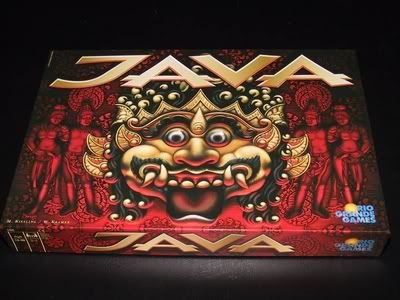

If you thought Tikal was a beautiful game once completed, Java is just as visually impressive, if not more so due to its elevations. Ravensburger, with the graphical design of Franz Vohwinkel, printed the Java terrain tiles on amazingly thick cardboard. Despite their thickness, the tiles are cleanly die-cut and fall out of their frames with a gentle tap. The board is a four-fold linen finished work of art, depicting the undeveloped land of Central Java (in hexes) bordered to the north by mountains and to the south by a plain, with a scoring track running around it. The developers are similar to those used in Tikal, made of smooth wood and colored with earthy tones. The game also comes with some counters and the expected four Action Point menu cards. The only weakness of the package is the festival cards, which puzzlingly are small uncoated cards with square corners. One would have expected larger (say, Torres-sized) linen-finished cards with rounded corners in a package this lavish. This omission is a bit disappointing, but given how the rest of the game looks, it’s still a sight to behold.

The Game

Players have six Action Points on each turn. With these points, they develop Central Java by laying terrain tiles onto the board, they deploy and move developers across the land, they build and extend palaces and they prepare for palace festivals.

The terrain tiles are the main focus of the game. There are three-hex tiles (depicting two terrace hexes and one village hex), two hex tiles (one terrace and one village) and single hex tiles of each type. There are also water hexes for creating irrigation fields. The three-hex tiles and irrigation field tiles are placed in a common supply – all the players draw from this single supply. The two-hex and single hex tiles are given to players as their private supply. Players must play at least one non-water terrain tile of any kind in a turn.

Water tiles may only be laid directly onto the board. The terrain tiles may be laid upon each other, as long as a tile is not laid directly on top of an identical tile, and the tile is not placed on water. This allows players to build terraces skyward by overlapping tiles. You also can’t play a tile on a palace or hex occupied by a developer.

Players score in three ways. The first is by enclosing irrigation fields. Once an irrigation field is completely enclosed, the player with the developer on the highest level adjacent to the pool scores. If there is a tie, the player with the most developers on that level scores. If there is still a tie, no one scores.

The second is by building or extending palaces. Palaces are built in villages, and the size of the palace may not exceed the size of the village. The size of a village is the number of contiguous village hexes that compose the village. A player must have the developer at the highest level within the village to build or extend a palace. If there is a tie, most developers at that level may build. If there is still a tie, no one may build. A player whose developer builds a palace scores prestige equal to half the size of the palace. Palaces are sized from two to ten, even numbers only. If a village grows in size, then the palace may be extended to a larger size, and the player whose developer does this scores for the extended palace.

Once a palace has been built, the village becomes a city. Any player with a developer present in that city may hold a festival in the palace. This requires the use of festival cards. There is a reference festival card placed face up. Players play cards to match the symbol or symbols on the reference card. The player with the most matching symbols scores for the festival. Draws may be offered among the players if there is a tie. In this case, a smaller amount of prestige is garnered by the drawing players.

Once the final three-hex tile is played onto the board, the game enters a final scoring round. The player who played the final three-hex tile completes his turn, and then scores each palace where he has a developer at the highest (full points) or second-highest (half points) level in the city. The other players then take a final turn, scoring in the same fashion.

The player with the most prestige at the end of the game wins!

Strategy

By experience, the irrigation fields provide the quickest way to score points at the beginning of the game. Players tend to play as many irrigation tiles as they can while still being able to enclose the whole pool in the same turn. (Otherwise, the next player will take advantage of their hard work and score the irrigation field for themselves.) This has the unfortunate side effect of tattooing the board with three-hex irrigation pools all over the place, making it extremely difficult to build large cities. Even worse, players may concentrate the irrigation on one side of the map or the other, rendering that side of the map near-impossible to develop to any degree of satisfaction. Of course, that doesn’t stop anyone from doing it every game – it just ups the difficulty.

One of the neatest moves in Java, as well as one of the most powerful, is using a terrain tile to split an existing city. This allows a degree of reuse of large villages. Just separate the palace from the rest of the city and it becomes a village, ready to accept a new palace. This can be defended against by building palaces as centrally as possible, making it difficult to reuse a substantial portion of the city.

There are more defensive plays possible in Java. Players can deploy most if not all of their developers and post them in places where the restricted development and movement is desired. A board full of irrigation fields and developers is a hostile environment for building palaces of larger sizes. Players can also develop cities with multiple elevations, making it difficult and expensive (in terms of personal tiles) to split the city for further use.

Building palaces of sizes smaller than ten without a good defense is perilous as it allows the following player to extend the palace and score a larger number of points. When building a small palace, try to ensure that there are preventive measures against opponents who are wont to horn in on your action.

Always try to have a couple of festival cards in hand. If a player is up against opponents with no festival cards, he can get a freebie festival. Giving up points free is never advisable. Make it a point to draw two cards when you have one or no cards in hand. If the first card you draw doesn’t match the reference card, consider drawing the reference to guarantee at least one match. During a festival, it’s better to draw with one opponent than to get into a card battle that costs you two or more cards. For more festival card play practice, play Reiner Knizia’s Taj Mahal.

Finally, always be aware of when the final three-hex tile might be played. It’s difficult to go last in the final scoring round, especially if you’re caught unaware. If possible, prepare for the end of the game a couple of turns in advance by positioning your developers in all the cities on the board. Don’t be shy with your personal tiles, but try to hang on to a couple of the single hex tiles for use in your final scoring round. Java opponents can be a crafty lot, and the size ten palace that you thought was securely yours may be snatched from you with a couple of creative moves. If you can place your developer right next to the palace tile, do so. This prevents the guy from getting separated from the palace due to a city split.

Reviewer’s Tilt

We love the design of Java. It’s got a very strong theme, coupled with an amazing tile-laying mechanism that keeps me thinking about moves constantly. My group has a lot of fun with Java. If I had never played Torres, I suspect that it would be in my top ten favorite games. Java is beautiful, it’s challenging and it brings out creativity and cleverness in players. Granted, some people will have difficulty with this type of game. It’s a spatial affair coupled with a wide-open action structure, two elements that can cause some gamers to freeze. However, with the right group, it’s one of the best German games.

I believe that Java plays best with three players. Each player has more control, the turns come around faster, and the timing of the final scoring round is easier to handle. This doesn’t decrease the playing time though, since all the three-hex tiles still have to be played. Java is ok as a game for four, but it becomes more difficult and to some, more frustrating. I don’t like it much as a two-player game due to the terms of the final scoring round, but it is certainly playable with two.

If you’ve been scared off by Java’s reputation, give it a chance, especially if you enjoy Torres or Tikal. It’s not an easy game, but it’s not as difficult for most people as its reputation suggests. As a choice for the heavier end of the spectrum, Java is an excellent addition for most German strategy game collections.

No comments:

Post a Comment