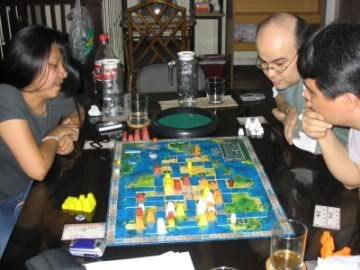

Mexica comes in the same size linen-finished box that its older siblings did, complete with the amazing insert with a place for everything. The board stunning, a four-fold linen-finished affair depicting and island subdivided into squares. The players’ Mexicas and scoring cubes are colored wooden pawns. The game’s tiles are well-made smooth cardboard pieces. The game has the familiar Action Point menus. The highlight of the package is the colored plastic monuments, with one-story to four-story models. The plastic is nice and sturdy, and has a nice detail of the monument designs. (All they’re lacking are the virgins and bloodstains.) All in all, Mexica is another luxurious package from Ravensburger and graphic designer Franz Vohwinkel.

The Game

Each player is represented by a Mexica on the board. Each player also receives a set of monuments to be built. Finally, a set of Calpulli tokens are laid out. Funny name, what do they do?

The Calpulli tokens (these are hexagonal tiles) define the objectives of the Mexicas. Each token has three numbers, in descending value. The first number defines the size of a district (in squares) that must be delineated with canals in order to found it as a neighborhood. This is also the number of points that the founding player gets for the neighborhood. Once a player encloses a district of the requisite size, he takes the appropriate Calpulli token and places it anywhere within the new neighborhood. We’ll get back to the Calpulli tokens later.

On his a turn a player gets six Action Points to spend on actions. Players can move their Mexica, lay down canals (which are a common resource, and come in one-square or two-square varieties), build bridges across canals or build monuments. They can also save their points, max two per turn, for later use by buying action tokens.

The heart of the game is Mexica movement. These guys are relatively slow of foot when traveling overland. It takes one AP to move them one square, and they can only move orthogonally. They can’t swim (which explains the bridges). However, they have two special modes of movement that get them places fast. The first is the bridge move. Mexicas have the power to travel down waterways, from bridge to bridge. All they have to do is get on a bridge, and find another bridge that can be traced directly down canals or even through the sea. For one AP, they can then use their power over the waterways to get them to the target bridge. This is a very interesting mechanism, and figuring out how to use the waterways to save movement AP is one of the most entertaining parts of the game. The other special movement ability is the island teleport. By channeling their power (expending 5 AP in the process), Mexicas can teleport to any empty land square or bridge on the island. It’s really expensive, but sometimes it’s the only option, especially if your Mexica has been trapped by his opponents.

So. Mexicas play down canals to enclose spaces that fit the requirements of the Calpulli tokens, and found neighborhoods. Once the neighborhoods are founded, the game’s secondary mechanism comes into play. Control of the neighborhood is determined by how many monument stories each Mexica is able to build in it. At the end of the phase, the Mexica with the most monument stories in a district earns victory points equal to the highest number on the neighborhood’s Calpulli token. Second and third most earn the two lower point awards on the Calpulli token. Tied players earn the higher award.

The game is played in two phases. The first phase ends when all eight Calpulli tokens are used to found neighborhoods, and at least one player has built all his monuments. At this point, monument scoring occurs, and a second ration of monuments is handed out. Seven more Calpulli tokens are laid out, and the game continues. The second phase ends when all Calpulli tokens have been used (or the remaining ones can’t be used due to how the board played out), and at lest one player has used all his remaining monuments. The game can also end when none of the players wishes to take any more turns. All the neighborhoods are scored as in the end of the first phase. Finally, any unfounded districts are scored. This is done by counting the number of squares in that unfounded district and awarding the points based on the majorities of monuments built in that unfounded district.

At the end of the final scoring, the player with the most victory points is proclaimed the land’s most powerful Mexica and wins the game!

Strategy

In most cases, it is initially a race to establish the larger neighborhoods. Care must be taken to not allow the player following to found a larger neighborhood than what your Mexica was able to do. When this is not possible for some reason, you can stall by moving your Mexica towards a coastline (to make founding a district easier by using the sea as a boundary) and saving two APs for use next turn. However, you may lose the initiative to build the juicier neighborhoods, so be careful. Remember that the Calpulli token becomes an obstacle when placed. You can use it to block convenient access points into your neighborhood.

Once all the larger neighborhoods are gone, it’s time to start staking out the place with monuments. There are three things to consider when building monuments. First, monument placement. Like the Calpulli token, monuments are obstacles that cannot be traversed by Mexicas. Use them to make access to your neighborhood more difficult. Second, the squares within a neighborhood are limited. If there are no more squares, no one else can build monuments and take the neighborhood away from you. (There will always be one empty square since a Mexica needs to stand in the neighborhood to build in it.) This is where the single-story monuments can come in handy – they can eat up space. Conversely, the four-story monuments are best used when the opponent has eaten up a lot of space with small monuments – you’ll need your larger ones to try to earn points. Finally, monuments are a component of timing the game end. If you’re ahead on points and control in the second phase, once the rush for the large neighborhoods is over try to see if building out will end the game before the other players have a chance to use all their monuments.

Mexica movement is fun and important. Once maneuver that can be overlooked is moving Mexicas down a canal feeding into the sea and reentering the island through another canal somewhere else. When considering a long journey across the board, weight the cost of teleporting against building a bridge and surfing. The surf maneuver might be cheaper. When the end of a phase is imminent, try to see if you can get your Mexica back to the staging area – the five points can be the margin of victory.

Reviewer’s Tilt

I like Mexica. It’s a fast game compared to its sibling, playing at about the same speed as its cousin Torres – 60 to 90 minutes for a four player game. However, that’s an important consideration – Mexica only works will with four players. Due to the scarcity of real estate, the three-tiered monument majority mechanism and the interesting situations created by blocking tactics, it loses a lot when played with three. I wouldn’t recommend it at all with two.

Another important characteristic is that Mexica has no luck at all. There’s a bit of randomness from the Calpulli token layout, but it favors no player and serves to make each game different. At that, it succeeds admirably.

There is a lot of opportunity for defensive play. This makes Mexica a decent middleweight strategy game, much more so than Tikal, but just slightly less than Java. It also has a touch of the spatial nature of Java and Torres stemming from the founding of neighborhoods and the movement of the Mexicas.

I’d rate Mexica to be the second-best entry into the Action Point trilogy, significantly better than Tikal, but just less interesting than Java due to less depth. It does play to completion in 30 to 60 minutes less time than Java, so if deep brain-torching games aren’t a staple in your game group Mexica should be a good candidate for your shelf. Look up Torres first if you’re new to the Kramer/Kiesling Action Point games – Torres is still the best of them by far.

No comments:

Post a Comment